Tackling Illness Through Art: An Interview with Christie Begnell

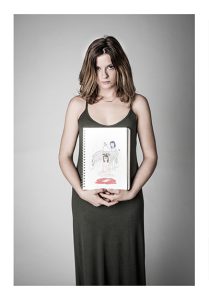

Photograph By Jennifer Blau

At WayAhead, we first met Christie Begnell as a participant in our Eating Disorders: Dispelling the Myths video installation at Parramatta Library for Mental Health Month last year. Christie is a 24-year-old occupational therapist and artist who has a lived experience of having an eating disorder (ED). Recently, she has been using her prodigious artistic talent to share her thoughts and experiences in books and on her popular Instagram account, meandmyed. Through her online presence, she has created both a community for other people with eating disorders to connect and support each other, as well as a resource providing others with insights into an often-maligned, often-misunderstood, yet very serious, mental illness. Christie spoke to us about her experiences creating art and writing a book about her eating disorder.

You initially started drawing to be able to share what you felt with your family and with healthcare professionals. What made you start sharing your art on social media and putting together a book?

Last year while I was an inpatient, I quickly became known as “the girl who was always drawing”. I found drawing to be the most therapeutic thing for me, as I could visually express what I couldn’t verbalise. Eventually the therapists asked me about what I was drawing, and they took a keen interest in my artworks. One therapist actually asked if she could photocopy some of my drawings to use with her clients. It was that same therapist who suggested I put all of my drawings together as a book. I was a bit hesitant about the idea to begin with, but once they convinced me that it’d be helpful for other people with EDs, I was raring to go.

In regards to sharing it on social media, @meandmyed.art initially just became a way of promoting my book, but as I was still navigating early recovery, I still needed to draw in order to cope. I figured I may as well share what I was drawing, as I followed so many inspiring artists on Instagram and I aspired to be like them. My account is now a whole lot more than just a way to promote my book. It’s a platform for me to support others, to provide recovery resources, to provide psychoeducation and help challenge ED and mental health stigmas. Most importantly though, my account has become a place for my followers and myself to connect and remind ourselves why we’re enduring this pain to recover.

Recent research has found that teens rate Instagram as having the most negative impact compared to other social media sites. Instagram scored particularly negatively on body image and FoMO (fear of missing out), but also particularly positively on self-expression and self-identity. What have your experiences on Instagram and other social media sites been?

Social media can be a very deceiving reflection of a person’s true life. I’ve followed many people who present themselves as being more fulfilled than they actually are. In my experience, that happens more on Instagram than Facebook. That might have to do with the fact that Instagram seems to be more of a popularity contest than any other social media platform. There’s a big unspoken competition to get more followers and more likes on your pictures. Being in that online environment would certainly cause people to filter out the bad. As for poor body image, there are A LOT of fitness models and young girls using their bodies as a means of gaining more followers and attention. That doesn’t happen so much on Facebook, because you usually have your family as friends, and they can see and comment on everything you post.

My experience with Instagram however has been very positive, especially within the body positive community. There is a whole world of female role models with different shaped bodies showing us that we can love ourselves regardless of what we look. This movement has changed my relationship with my body so much. Before discovering the body positive (bopo) community on Instagram, I only ever saw what is represented in mainstream media, which is always “you have to weigh x kg, and fit into x clothing size before you can love your body”. This, again, isn’t as accessible on Facebook, because most bopo accounts (men and women) have started and have built themselves up on Instagram.

As for the hate I receive, it has been interestingly worse on Facebook. I’ve had a lot of people try to argue the whole “obesity is unhealthy” point on Instagram whenever I preach self-love at larger sizes. For me, that point is merely an excuse these people use to justify their bullying online. It is heartbreaking to see some of these bopo accounts get messages telling them to die, etc. when all they are doing is existing and being good role models for young girls. The nasty feedback I’ve had on Facebook has started from having articles shared about me on Buzzfeed, The Daily Mail, etc. People claiming that my illness isn’t real and that my artwork is amateur. To me, it makes no sense that people would be nastier on Facebook, as they can’t hide behind an anonymous account like they can on Instagram.

What role do you think social media can play more broadly in its contribution to good mental health?

I’ve noticed social media working best when it is challenging mainstream media, and filling in the gaps that mainstream media so often leaves. So many people use social media, but it is still filled with trashy stories, quick sales and images that make us feel insecure in ourselves. Social media should bring people together and empower them. It should be informative and interesting. It should be interactive and create communities where people feel safe expressing themselves and seeking help. Most importantly though, it should be honest.

Posting a picture of a fit woman in a bikini, while visually pleasing, isn’t doing any of the above things. On the other hand, posting a picture of a woman in a bikini who is insecure in herself, but is sharing her insecurity with the world while trying to find confidence, is. I know media is all about sales and viewers, but if it’s putting us at risk of decreased mental health, it’s not working properly.

You have a really interesting background, including a Bachelor is Health Sciences, a Masters in Occupational Therapy and you’re currently undertaking a Masters of Psychology. How does your academic background inform your drawings?

My education has been a huge help. It has given me the ‘clinician perspective’, which guides a lot of my drawings and the recovery tools I make. I now understand how mental illness functions on a physiological level, and I’m gaining more and more insight into why somebody might behave in a particular way. I try to put what I know into interactive and accessible illustrations/guides, because when it comes to EDs, there’s really nothing else like it out there. I would’ve loved to have had visual resources like mine while I was first developing my illness.

What do you think the most important things are for carers, families and healthcare professionals to know about the experiences of someone with an eating disorder?

I think it’s really easy to forget that people with EDs are really just terrified. Having a voice inside your head telling you to starve yourself to death is hard, and rebelling against the voice by doing something like eating, just makes it worse. For the majority of us who have EDs, we’ve been through really difficult, and sometimes traumatic periods of our life, and living with this illness is like experiencing trauma over and over again. When we lash out, get angry, become manipulative, and withdraw, we do so because we’re terrified of being hurt, and this is the only way we know how to protect ourselves.

The most important thing to practice is patience. Recovery takes time.

And finally, what are the things that you hope change regarding the way we, as a society, think and talk about eating disorders?

We need to stop viewing Eating Disorders as glamorous, or as something young, white girls develop to get attention. When we only talk about eating disorders when a celebrity loses too much weight, we paint the picture of a fad diet and obsession with body image.

I want society to learn about Eating Disorders as deadly mental illnesses with a strong biological basis. I want them to know that anorexia is not the only classification and that men and women of all ages, and cultural backgrounds experience them. It’s especially important for society to understand that weight does not indicate the severity of an Eating Disorder. People die from Eating Disorders at healthy and larger weights. We should not be laughing at people and turning them away from services because they’re not underweight. It is not acceptable to be excluding people with mental illnesses because they physically appear healthy.

I want all health professionals to have to undergo mandatory education in Eating Disorders in the way of either workshops, in-services or online activities that can contribute to professional development. If everybody, both professionals and society, can understand what Eating Disorders are and how they should be treated, we can tackle the stigmas surrounding them, and achieve better health outcomes.

By Tasnim Hossain

Newsletter

Stay up to date

Sign up to our Mind Reader newsletter for monthly mental health news, information and updates.