Virtual reality (VR) has recently exploded into the consumer world with devices like the HTC Vive, Oculus Rift, and Samsung Gear. It refers to the complete immersion within a virtual environment, so that users are able to virtually move, touch, and experience various stimuli. Popularised within the gaming industry, VR has enabled gamers to control virtual characters through their own physical movements, allowing a deeper and more immersive experience with the game. However, the increasing accessibility of VR has also opened up other possibilities and applications that were not previously tangible.

VR has allowed for more accessible and novel methods for treating different kinds of mental health issues. Cognitive-behavioural therapy (CBT) is typically used for the treatment of anxiety disorders. A vital component of CBT requires patients to undergo exposure therapy in order to confront stimuli that trigger their anxiety or phobia, whilst preventing the use of defence or safety mechanisms. There are an endless number of situations where anxiety can arise, such as social situations (interviews, public speaking) and phobias (fear of heights, spiders, small spaces), so creating real-life environments for exposure therapy can be extremely inefficient and impractical.

VR has allowed for more accessible and novel methods for treating different kinds of mental health issues. Cognitive-behavioural therapy (CBT) is typically used for the treatment of anxiety disorders. A vital component of CBT requires patients to undergo exposure therapy in order to confront stimuli that trigger their anxiety or phobia, whilst preventing the use of defence or safety mechanisms. There are an endless number of situations where anxiety can arise, such as social situations (interviews, public speaking) and phobias (fear of heights, spiders, small spaces), so creating real-life environments for exposure therapy can be extremely inefficient and impractical.

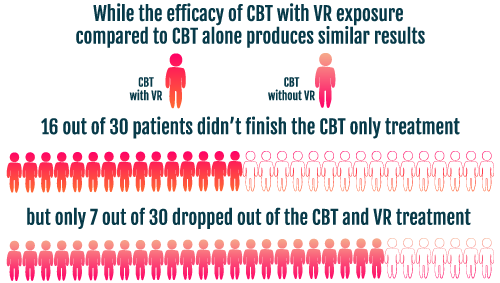

VR technology overcomes these limitations by providing patients with a fully immersive environment, albeit, virtual in nature. Penate-Castro et al. (2014) analysed the efficacy of CBT with VR exposure compared to CBT alone amongst patients suffering from chronic agoraphobia. The VR component of this study involved exposure to four virtual environments, including an airport, elevator, beach and carpark, which caused the patient the most anxiety. Penate-Castro et al. (2014) found that both treatments showed significant clinical improvement post-treatment and six months later. The interesting findings were the treatment dropout rates of CBT against CBT with VR exposure. Of the thirty patients undergoing CBT alone, sixteen out of thirty patients dropped out (53.33%), as opposed to only seven of thirty patients dropping out of the CBT with VR exposure treatment (23.33%). Greater adherence rates within the VR exposure group suggest that the approach was less confronting for patients, whilst still providing significant clinical improvement in anxiety levels. These findings have also been supported with studies involving patients suffering from social anxiety disorder (Bouchard et al., 2017), post-traumatic stress disorder (Rothbaum et al., 2014), and schizophrenia (Rus-Calafell et al., 2014).

The possibility of significant clinical improvement in CBT treatment with VR exposure is promising. Virtual environments can be developed and tailored to a patient’s specific needs, as opposed to real-life scenarios where there are variables that cannot be controlled. Furthermore, it appears that using a fully immersive virtual environment does not lose any of the vital components required for exposure therapy, suggesting that VR is just as effective for treatment. As a result, utilising VR technology can be significantly more practical, cost-effective and time-efficient.

Although there is significant evidence to support use of VR for exposure therapy, there is limited evidence for its use in treating other mental health disorders. To date, there are only two studies examining the use of VR and depression (Shah et al., 2015, Falconer et al., 2016), both preliminary studies examining whether VR can be utilised as a medium. VR has also been used to treat eating disorders, with the idea that VR can help with body image, but so far, such studies have not been considered methodologically sound (Freeman et al., 2017).

Considering that VR has only recently gained popularity and widespread use, more time is needed before we can utilise the technology as an effective medium for the treatment for mental health. However, the practicality, effectiveness and cost efficiency of VR provides a promising outlook on delivering significant improvements to mental health.

By Johnny Wang

References

- Bouchard, S., Dumoulin, S., Robillard, G., Guitard, T., Klinger, É., Forget, H., … & Roucaut, F. X. (2017). Virtual reality compared with in vivo exposure in the treatment of social anxiety disorder: a three-arm randomised controlled trial. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 210(4), 276-283.

- Falconer, C. J., Rovira, A., King, J. A., Gilbert, P., Antley, A., Fearon, P., … & Brewin, C. R. (2016). Embodying self-compassion within virtual reality and its effects on patients with depression. British Journal of Psychiatry Open, 2(1), 74-80.

- Freeman, D., Reeve, S., Robinson, A., Ehlers, A., Clark, D., Spanlang, B., & Slater, M. (2017). Virtual reality in the assessment, understanding, and treatment of mental health disorders. Psychological Medicine, 1-8.

- Peñate Castro, W., Roca Sanchez, M. J., Pitti González, C. T., Bethencourt, J. M., de la Fuente Portero, J. A., & Gracia Marco, R. (2014). Cognitive-behavioral treatment and antidepressants combined with virtual reality exposure for patients with chronic agoraphobia. International Journal of Clinical and Health Psychology, 14(1).

- Rothbaum, B. O., Price, M., Jovanovic, T., Norrholm, S. D., Gerardi, M., Dunlop, B., … & Ressler, K. J. (2014). A randomized, double-blind evaluation of D-cycloserine or alprazolam combined with virtual reality exposure therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder in Iraq and Afghanistan War veterans. American Journal of Psychiatry, 171(6), 640-648.

- Rus-Calafell, M., Gutiérrez-Maldonado, J., Ortega-Bravo, M., Ribas-Sabaté, J., & Caqueo-Urízar, A. (2013). A brief cognitive–behavioural social skills training for stabilised outpatients with schizophrenia: A preliminary study. Schizophrenia research, 143(2), 327-336.

- Shah, L. B. I., Torres, S., Kannusamy, P., Chng, C. M. L., He, H. G., & Klainin-Yobas, P. (2015). Efficacy of the virtual reality-based stress management program on stress-related variables in people with mood disorders: the feasibility study. Archives of psychiatric nursing, 29(1), 6-13.