Follow Up Story

“When we talk about how Australia treats our criminals, often the discussion is about the niceties or otherwise of prison facilities…we don’t talk enough about whether they should be in prison at all”. This is what Andrew Leigh said in his recent speech to the Justice Connections Conference 2015 and he makes an interesting point. Is incarceration always the answer and if not, what are our alternatives?

In his conversation with Brett Collins, Harry Easton looked at the way in which the environment of prison can create a situation in which mental illness develops. However, what about those individuals who already suffer from a mental illness when they commit the crime? Does our justice system need to find a new way of helping them?

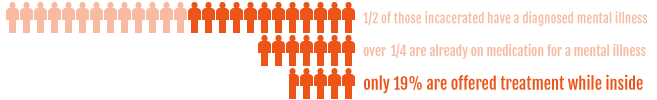

One of the greatest issues when talking about the correlation between mental health issues and crime is the danger of overgeneralisation. That is, making it sound like any individual with a mental health issue is highly likely to be a potential criminal. This we know is simply not true. However, it is undeniable that mental health issues are over-represented in the prison community and this is an issue that needs to be dealt with.

According to the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW), almost half of those incarcerated have been told by a health professional that they have a mental illness and more than a quarter are on medication for this. However, only 19 per cent of prisoners are offered treatment for mental health conditions while behind bars.

There are various reasons for the rise in mandatory sentencing laws, which effect and limit judicial discretion, and an increase in ‘imprisonment-in-lieu’ orders, where individuals are imprisoned in-lieu of paying back overdue fines. The way in which these two practices work make it difficult for judges to adjust sentences to account for personal circumstances, financial situation, substance abuse, previous convictions and mental illness.

If the toll this takes in human suffering is not enough to consider a change of practice, it is also worth looking at the economic detriment of our current prison system. The average prisoner in Australia costs the taxpayer almost $300 a day and, according to the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS), in 2009 over half those in prison had been imprisoned before. Not only is this an economic disaster but it goes to show the current system is not wholly effective in dealing with the issues that cause individuals to offend in the first place.

If the toll this takes in human suffering is not enough to consider a change of practice, it is also worth looking at the economic detriment of our current prison system. The average prisoner in Australia costs the taxpayer almost $300 a day and, according to the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS), in 2009 over half those in prison had been imprisoned before. Not only is this an economic disaster but it goes to show the current system is not wholly effective in dealing with the issues that cause individuals to offend in the first place.

“Some people worry that focusing on rehabilitation as opposed to harsh or mandatory sentencing amounts to being ‘soft on crime,’” Mr Leigh said. “[But] studies show that increasing the size or the severity of the prison sentence does not correspondingly strengthen their deterrence effect.” Instead, Mr Leigh believes it is important to look at other methods of dealing with crime.

Those in the industry have long recognised community-based treatment is an effective and alternative way of dealing with those at risk of offending due to mental illness.

David Peters, deputy chief executive of Mental Health Carers -ARAFMI, believes, “Community support is always going to be a more effective way of helping people to effectively function in the community they live in.”

While he recognises community programs are not appropriate in all cases, he believes that an increase in these programs would be hugely beneficial to those individuals who have found themselves in prison. This is especially the case for crimes that could have been avoided through early intervention programs and access to adequate community support facilities.

While he recognises community programs are not appropriate in all cases, he believes that an increase in these programs would be hugely beneficial to those individuals who have found themselves in prison. This is especially the case for crimes that could have been avoided through early intervention programs and access to adequate community support facilities.

“We all progress through life with the support of others,” Mr Peters says “and maybe this support will build people up enough, give them the confidence to make a change in their lives.”

One way of promoting the idea of community-based rehabilitation programs that has been championed by both Mr Leigh and fellow shadow minister Shayne Neumann, as well as various economists throughout the country, is the idea of justice reinvestment.

Justice reinvestment is based on the idea that a large majority of offenders come from a relatively small number of disadvantaged social groups. It reasons that the money spent incarcerating these individuals when they offend would be better spent on preventative methods and programs throughout those communities that are at risk.

The idea is to spend money on community support programs to target those individuals at risk of incarceration and those coming out of prison who are at risk of reoffending. And it seems to work.

In 2007, Texas introduced its Justice Reinvestment Initiative, which Governor Rick Perry said would aim to “focus more resources on rehabilitating those offenders so we can ultimately spend less money locking them up again.” The scheme saw an increase in treatment and diversion funding to $241 million, saving $443 million through reducing the need for bed space and new prison construction, thereby significantly reducing the rate of recidivism.

In 2007, Texas introduced its Justice Reinvestment Initiative, which Governor Rick Perry said would aim to “focus more resources on rehabilitating those offenders so we can ultimately spend less money locking them up again.” The scheme saw an increase in treatment and diversion funding to $241 million, saving $443 million through reducing the need for bed space and new prison construction, thereby significantly reducing the rate of recidivism.

However, the distribution of money throughout the justice system is a difficult and multi-faceted issue; one that requires political cooperation on multiple levels as well as research into the best way of investing in community support programs.

Overall, there needs to be greater awareness on a number of issues related to the Australian justice system, mental health and the individuals caught up in the former as a result of the latter.

Jean Roxon

View the original story HERE