Naz Jacobs looks into the work of SSI, an award winner at 2015’s Mental Health Matters Awards for Culturally and Linguistically Diverse Communities

“The essentials of happiness”, the saying goes, “is someone to love, something to do, and something to look forward to.”

Unfortunately, for refugees and asylum seekers in Australia, these concepts can feel far out of reach. Many have left their families behind, often cannot find immediate employment, and are highly uncertain about their future.

Settlement Services International (SSI) is a leading provider of community integration and settlement services for refugees and asylum seekers in NSW. At the end of September, SSI was presented with the 2015 Culturally and Linguistically Diverse (CALD) NSW Mental Health Matters Award.

Over the last year, SSI has successfully implemented the Refugee Health Screener tool (RHS-15), which identifies the mental health needs of their clients and allows greater access to support services.

David Keegan, manager of Humanitarian Services at SSI, says, “We didn’t expect to win it, so it was great to be acknowledged and for refugee mental health to get some exposure.”

SSI provides various forms of support to about 12,000 clients per year. Through dealing with their clients, they found that many experienced symptoms of depression and anxiety largely due trauma, grief, and problems with resettlement.

However, SSI also found that despite the prevalence of mental illness within the groups they worked with, there was a lack of solid evidence regarding the cases of mental illness in refugees and effective forms of treatment. This lead to the implementation of the Refugee Health Screener tool (Hollifield et al., 2013) developed in the US.

Since August 2014, SSI has conducted over 7,500 assessments.

Keegan says, “We looked at our referral rates to psychological services from before and after using the screening tool, and referral rates had doubled.”

Nevertheless, despite the increase, 66% of those referred refused or did not give consent to engage in professional help. The reasons clients gave for this were mostly associated with denial, or immense stigma and shame within their communities.

One of our biggest struggles,” says Keegan, “is helping refugees see that managing and looking after your mental wellbeing is just as important as trying to make sure you have a house and that your physical wellbeing is good, and so forth.”

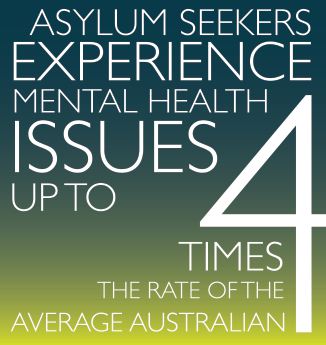

SSI found that refugees and asylum seekers experience mental health issues up to four times the rate of the average Australian.

SSI found that refugees and asylum seekers experience mental health issues up to four times the rate of the average Australian.

Many experience trauma through violence in their home countries, or through a lengthy process of fleeing and passing through multiple countries where they lack safety and legal status. Once settling in Australia, they then face challenges including learning English and understanding how Australian laws and social systems work. News about conflict in their home countries is also an added stress as they worry about the safety of the family and friends they have left behind. All of these factors add to the vulnerability and likelihood of refugees and asylum seekers experiencing anxiety and depression.

Keegan says, “Another thing we’ve found with many people who we’re working with at the moment, is that they’ve been in successful jobs and owned businesses in their home countries. They’ve had to leave all that behind to come here, and they almost start at the bottom of the rung again. So getting into work can be really difficult for some people and can really affect their morale.”

The high incidence of mental health problems wasn’t the only outcome of SSI’s research. There have been other interesting findings that require further analysis.

One pattern that SSI noticed was that clients tended to report higher levels of distress during times of negative media attention towards refugees or asylum seekers. Public attitudes and changes in government policy affected clients and increased levels of anxiety. Asylum seekers were especially vulnerable to this, as their immigration status was still uncertain and they were unsure of their place within Australian society.

Another finding yet to undergo further analysis is clients perhaps experiencing less distress in earlier periods of their resettlement due to being in ‘survival mode’, and greater distress kicking in later as a delayed reaction.

What we tend to see — and this is anecdotal, from talking to case managers and looking our incident reports and so on,” says Keegan, “Is that once clients have secured housing or start to feel a sense of stability, that’s when the effects of the trauma tend to present themselves more.”

“And that’s fairly consistent with trauma theory that people in survival mode tend to cope, but when things become better, they tend to feel worse. That’s when the effects of the trauma start to come out, and people start to really think, ‘Oh gosh, what have I just been through.’”

Written by

Naz Jacobs

SSI have recently partnered with the University of NSW to work on further research and analysis centred around the mental health of refugees. In the meantime, they hope to continue raising awareness about the importance of understanding mental health in migrant groups, and providing services dealing with their specialised needs.

Back to most recent edition