It’s Summer Time: We Need to Talk About ‘Summer Bodies’ and Body Image

Summer is now officially here, with the weather warming up around Australia. As the layers are shed and people start heading towards the beach, certain phrases start cropping up:

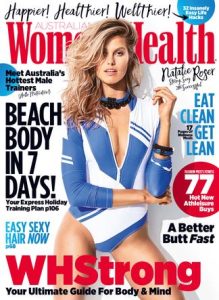

“Get Your Summer Body Now!” from Oxygen Magazine.

To be fair, other magazines do fare slightly better: “Crush Your Life Goals: Get a strong bod” Cosmopolitan

But from magazine covers to TV to the online sphere, there are strong social cues that it is summer time and that your body needs to look a certain way to enjoy it.

WayAhead spoke to the Butterfly Foundation, an organisation dedicated to providing support for people with disordered eating and body image issues, about this phenomenon and the risks of this increased pressure on body image across both on social media, traditional media and other advertising platforms.

“Over the festive season, Butterfly’s National Helpline tends to see an increase in the number of calls and webchats. There is an increase in advertisement and hashtags focusing on ‘bikini bodies’, ‘shredding’, ‘summer bodies’, dieting and exercising. We have constant access to images of people, their food, their lives and quite frequently their bodies,” a spokesperson for the Butterfly Foundation said.

“This can lead to unhelpful comparisons, pressure to achieve a certain body type and may contribute to body dissatisfaction. Advertisements such as these may encourage [people] to ‘fix’ or ‘alter’ their appearance rather than seeking health professional advice,”

Dr Jennie Small, a Senior Lecturer at the University of Technology, Sydney, wrote a research paper last summer analysing the phenomenon of women’s “beach body” in Australian magazines. Dr Small’s research found that throughout the year, women’s magazines focused on women’s bodies in a myriad of ways – hair, skin, make-up, body shape and clothing – but during the summer, the focus was specifically on the “summer beach body”. The magazines implied that women’s bodies are on display during the summer, and by repeatedly showing pictures of slim, toned muscles and fit bodies in bikinis, these magazine covers targeted women’s feelings of insecurity which ultimately made it easier for marketers to sell things to women.

In fact, the popular concept of a “bikini body” was actually created as part of a marketing campaign from the 1960s for a weight loss company called Slenderella. Their tagline at the time it was created was: “High firm bust – hand span waist – trim, firm hips – slender graceful legs – a bikini body!”

While these specific words are no longer as widely used, the concept of a bikini body remains fairly similar. This is reflected in Dr Small’s research, which concluded that the favoured body shape is slim (no larger than an Australian size 12), toned, tanned and fit. Dr Small recognised that the characteristics of the summer body have broadened in recent years, but the changes have been slight.

Advertising in Australia is mostly self-regulated with a code of conduct. While the code adopted by the Australian Association of National Advertisers (AANA) regulates the use of models in bikinis, the regulation itself refers to the use of nudity and whether the portrayal of people depicted is discriminatory. The code does not have clear guidelines on how bodies are portrayed and how this may negatively affect viewers. Many of these marketing images, which come under this regulation, and the ones on social media, which do not, are professionally shot, airbrushed or digitally enhanced. It is unrealistic for viewers to compare they way they look to these models and social media influencers.

The Butterfly Foundation recognises that there is a positive aspect to social media through raising awareness around good mental health and wellbeing, and through creating spaces where people can connect and reach out for help.

However, they also recommend that people consider which accounts they follow and that it might be helpful to unfollow accounts that raise uncomfortable feelings or comparisons.

“Monitor the changes in your mood after doing this – it’s a simple change but an effective way of controlling what we are viewing and its influence on our self-esteem and body image,” a spokesperson for the Butterfly Foundation said.

If you, or anyone you know is experiencing an eating disorder or body image concerns, you can call the Butterfly Foundation National Helpline on 1800 33 4673 (ED HOPE) or email support@thebutterflyfoundation.org.au

By Cindee Duong

Back to most recent edition

Newsletter

Stay up to date

Sign up to our Mind Reader newsletter for monthly mental health news, information and updates.